I always find it peaceful and addictive to stand on the beach and look out into the horizon knowing that the denizens of the ocean are busy going on about their daily activities. My determination to work in the field of marine conservation landed me an opportunity to study some of the most fascinating and feared marine vertebrates – sharks and rays. My field sites included three harbours across India’s coastline, where I visited fish landing centres and interacted with the local fishers. The experiences gained by visiting these three places exposed me to a very different side of wildlife conservation and also gave me a first-hand experience of working in this field.

I originally planned to explore the genetic connectivity and diversity of common shark and ray species along the eastern and western coasts of India. Genetic diversity indicates the diversity at the molecular level across individuals of a particular species, most likely separated geographically, for example, the silky shark which is found in the Indian and the Atlantic Ocean. Protecting genetically diverse populations of a particular species ensures its continued survival as the species is buffered against the effects of a changing environment.

Silky shark off the Cuban coast. Photo by Christian Ferrer (Wikimedia Commons).

My first field site, Malvan (Chivla beach), is a small coastal town on the west coast of India. It is a tourist hotspot but far less crowded than the beaches of Goa – which itself is not far away from Malvan. The other two study sites, Chennai and Kochi on the east and west coast of India respectively, were much larger. My working hours for tissue sample collection were early mornings or evenings when fishermen landed their catch and held auctions. I was required to cut a small tissue from the dorsal fin of the animal and convincing fishermen in all three harbours to allow me to do this was not easy.

A scene from morning auction at Malvan. Photo by Sudha Kottillil.

The landing site in Malvan was an open market, close to where the Arabian Sea gently touched the shore. I was perplexed initially by the bustling shores filled with cacophonies of sellers and their agents, but these difficulties soon ceased as time passed and everyone grew extremely friendly. Many of them even started greeting me with a smile. Sometimes, I would also come across quizzical tourists who were keen to know what I was doing.

People were fascinated by the diversity of sharks I told them of. I got to see a gravid (pregnant) spadenose shark with pups on my very first day. From then I would encounter either a new species of shark or a ray almost every day. Species like devil rays, longheaded eagle rays, bull sharks, blacktip sharks, leopard rays, scalloped hammerheads, guitarfish and many more were observed with some of them being caught routinely.

Chivla beach at sunset. Photo by Sudha Kottillil.

My next site was Kochi (south-west coastal city), where the harbour was chaotic, filled with huge sharks and rays thrown out of the boat and taken directly to different corners of the harbour for weighing and scaling. All the sharks and rays there were adults, and the entire system was very organised. I came across many unfamiliar species, like silky sharks, thresher sharks and tiger sharks (all of which were caught in huge numbers).

Apart from identifying shark species correctly, ensuring that I stayed out of the way of fishermen and agents was a big task in itself! As the days went by, and they understood the reason for my visits, it became easier for me to carry out my work as they would tell me where I could find my target species. The conversations lasted longer as well and varied from the problems they faced to sharing their favourite seafood recipes!

Morning scene at Cochin Fisheries Harbour. Photo by Sudha Kottillil.

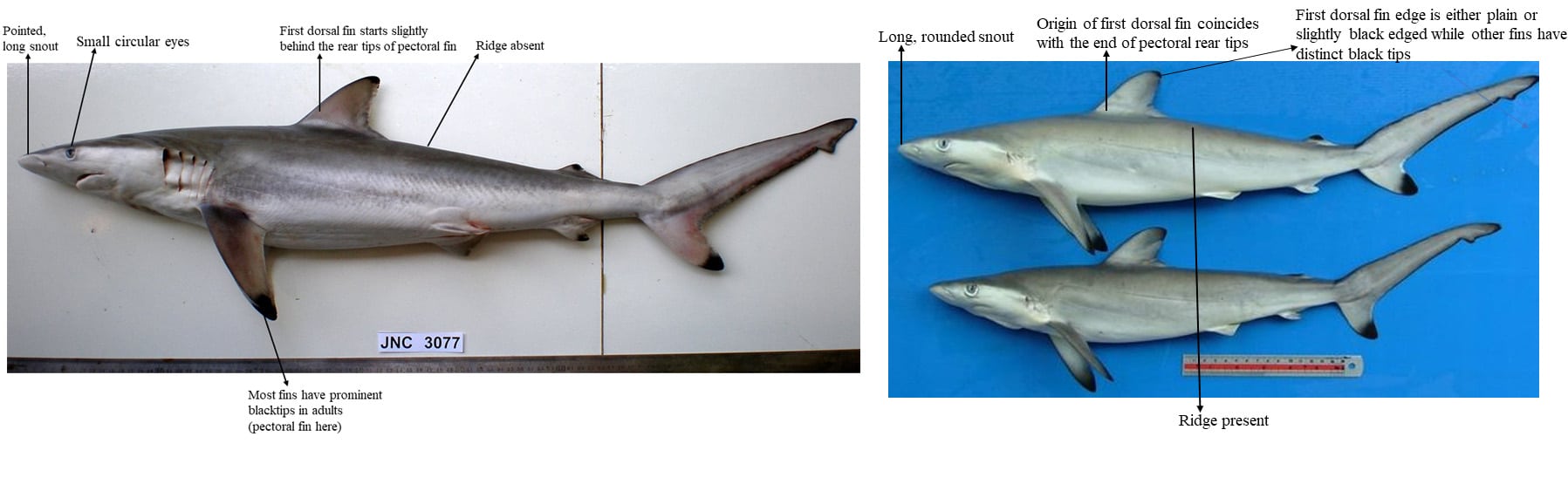

My final site was Chennai on the eastern coast, which was also the toughest of the lot due to the very early morning auctions and the hesitant fisherfolk. Most of them did not allow me to collect tissues and some were reluctant to even let me take measurements. Apart from the harbour, I had to visit three fish markets in order to give myself a better chance of collecting samples. One of the most difficult parts of the fieldwork was to identify sharks correctly as many of them, especially those belonging to the Genus Carcharhinus, differ by minute differences in their morphology. The species composition in Kochi and Chennai were similar with thresher sharks, hammerheads and silky sharks being encountered frequently.

Fishing Harbour in Chennai. Photo by Sudha Kottillil.

Some species are hard to differentiate morphologically.

Left: Carcharhinus brevipinna (spinner shark) from a fish market in Nouméa, New Caledonia. Photo by Jean-Lou Justine (Wikimedia Commons)

Right: Carcharhinus sorrah (spot-tail sharks) at Phuket Fishing Port, Thailand. Photo by Tassapon Krajangdara (Wikimedia Commons)

Throughout my journey, all the interactions I had with the local fishing community indicated that they are often confused about the policies governing conservation; they even find it difficult to identify certain protected species at times. The lack of flow of information between local communities, scientists and policy-makers often results in poor management of marine resources. However, since livelihoods of fisherfolk depend on marine resources, they hold extremely valuable information about the coasts and the oceans and long term changes happening in them.

Tapping into such potential to augment our limited knowledge and working together to implement conservation actions is the need of the hour. Fisherfolks are and can further become the ‘humans of conservation’, because, without their cooperation, help and knowledge, efforts to conserve marine species would be impossible. On a positive note, with increasing awareness and combined efforts of several researchers, we are slowly learning a lot about the oceans and how we can become better stewards of it. The field experiences I had, have indeed changed the way I look at these widely feared yet amazing species.