Thunk, thunk. Another book, binder, notebook off the shelf.

I stood in front of a polished wooden bookcase in my childhood bedroom in Mexico City; the window next to me looked out over green trees. Five shelves groaned with the weight of twelve years worth of school supplies, old post, diaries, books and notebooks.

On that sunny Saturday, I was taking the plunge. A number of incoherent piles (also known as stumbling points) had migrated off the bookshelf and crept up at different points in my room. These piles were not helping to create the minimalist environment I needed to flourish in my serious, demanding PhD in conservation. This important scoping trip would set the stage for my research, and I needed to whoosh emails off with a satisfied sigh – and not send receipts or family photos fluttering to the ground.

It was time to winnow down these treasured possessions and make some space.

I understand not everyone considers their old school notebooks to be treasures, and it’s certainly true there was a lot of crap on that bookshelf too. A number of people had subtly suggested it was time to throw it all in a bin bag, but for me, gaining glimpses into what I noticed or how I put ideas down on paper at different points in life is fascinating, and not an experience to be trashed or rushed.

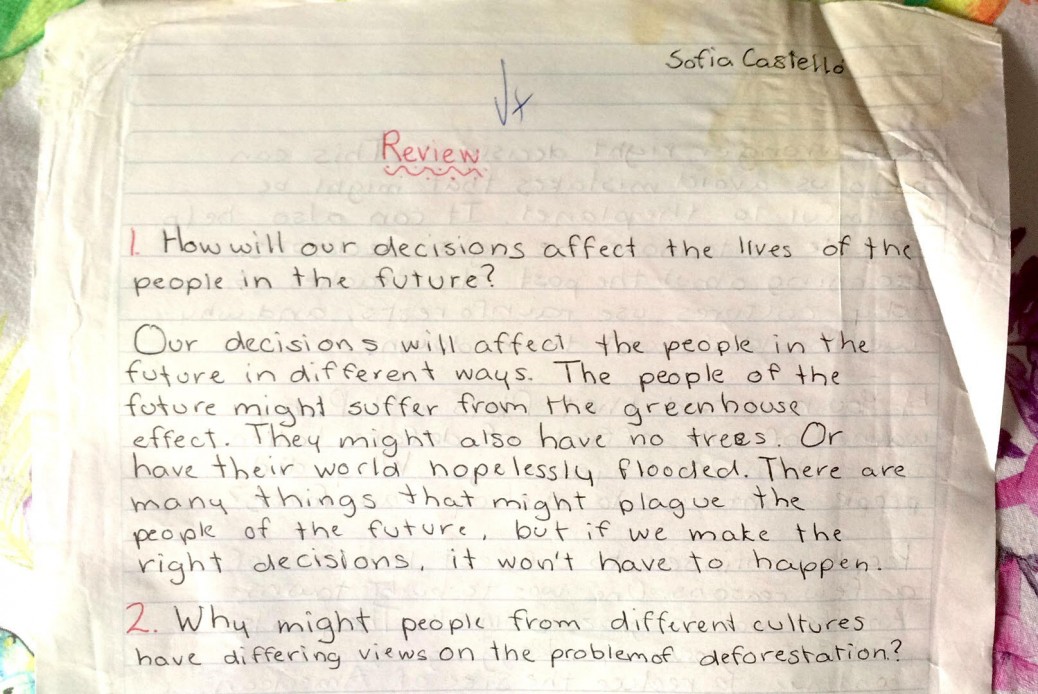

So I spent a full day sifting through useless piles and found a couple of treasures. One in particular, relating to conservation: a worksheet from when I was about 9, answering a series of questions about deforestation. It gave some serious insights into what I think of as conservation at the moment. And so it began:

“How will our decisions affect the lives of people in the future?”

Our decisions will affect the people in the future in different ways. The people of the future might suffer from the greenhouse effect. They might also have no trees. Or have their world hopelessly flooded. There are many things that might plague the people of the future, but if we make the right decisions, it won’t have to happen.

When it comes to conservation, I consider myself a bit of pessimist, with glimmers of optimism. It’s a profession that hinges, in some ways, on doomsday scenarios – and seeks to avoid them. Which is why I was surprised by the increasingly apocalyptic scenario I described and its twist at the end. It is surprisingly similar to the flow of thoughts that happens in my head around conservation today.

And finally:

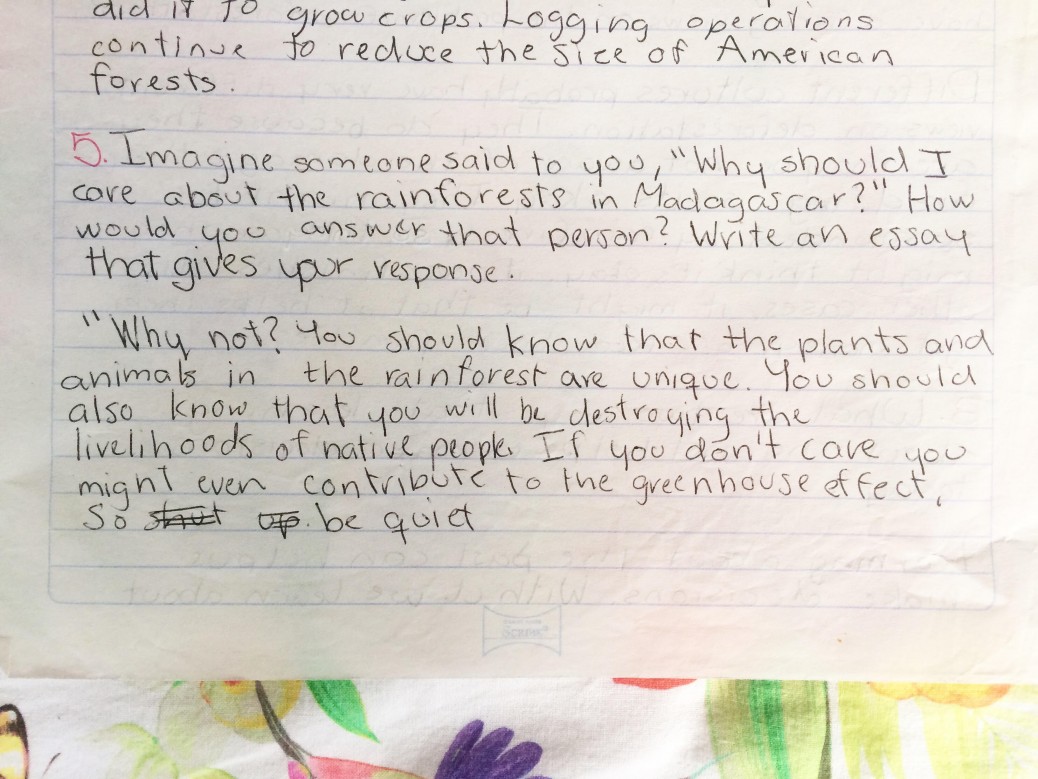

“Imagine someone said to you, “Why should I care about the rainforests in Madagascar?” How would you answer that person? Write an essay that gives your response.”

“Why not? You should know that the plants and animals in the rainforest are unique. You should also know that you will be destroying the livelihoods of native people. IF you don’t care you might even contribute to the greenhouse effect, so shut up be quiet.

My father always teased me that he was shocked by my venturing into ecology and conservation as a career, mostly based on the fact that I whinged on every camping trip we ever went on. This despite the warm sleeping bags, nice food, beautiful views. He was a dedicated conservationist, but we barely ever spoke about it. And that teasing has, on occasion, led me to wonder what on earth precipitated this career jump.

I tend to rewrite the story of my life according to my mood. When in existential crisis, I collect up my decisions and look at them (“objectively”) as isolated, uninformed, almost malleable points – wonder how things might have been different, how outcomes stacked into each other, what circumstances led into each point. It’s a dizzying array of strings and pictures, made manageable only by the limited scope of memory – the ability to see only 10 points at a time, say. And so a casual conversation or a picture I saw pops into mind and takes on great, defining importance. On occasion, I can’t fathom a reason at all.

When nothing logical comes to mind, as a purely hypothetical example, I might think: why did I decide to start a PhD in conservation?! If you really think about it, my topic is completely random. Why did I follow such a tiny, random little trail of breadcrumbs into an impossible endeavour?!

And so to discover this little piece of forgotten history, this evidence of a journey started long ago, was important. It reflected a brand of conservation similar to the one I believe in today, considering the importance of ecosystems, the uniqueness of species and the rights of local people. Finding it reminded me to have a little more faith in my thoughts and interests, my decisions and direction. I am grateful to my teachers. I also love how brash I was, how confident in my convictions – when now I sometimes feel I demur if people’s views don’t align with my own. Then again, I did downgrade my “shut up” to “be quiet”…

Perhaps what we think of as new is, in fact, old. Perhaps it’s pieced together and driven and accumulated over years of conversations, assignments, drawings, meetings we barely remember. Resurfacing this little point in my story reminded me that I led myself to this place for a reason, and to continue walking on the path – even if the breadcrumbs aren’t always visible.