If only you have ever watched a wildlife documentary you will be familiar with the marvellous migration of zebras and wildebeests across the crocodile-filled Mara river in the Serengeti-Masaï ecosystem. Let’s swap the savannah for endless steppes, the constant heat for glacial winters and arid summers, zebras and wildebeest for hundreds of thousands of small-sized gazelles. And let’s just forget about the crocodiles…

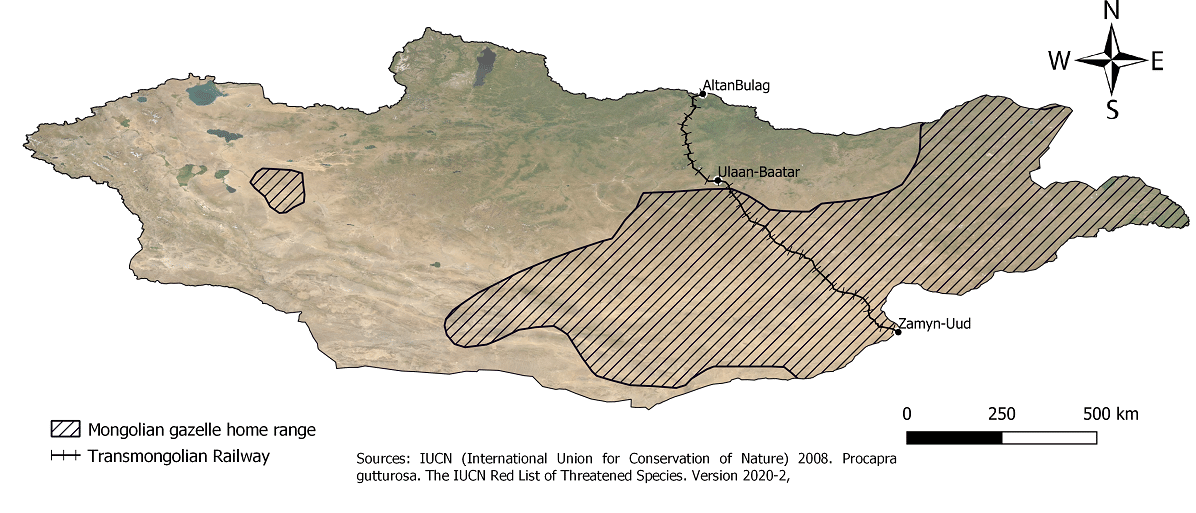

The nomadic migration of Mongolian gazelles in the steppes of Mongolia has been unhindered for millennia. That is the late 1950’s; the Trans-Mongolian railway was built, crossing Mongolia from Altanbulag in the North to Zamyn-üüd in the South-East. On both sides of the railway, fences were erected to prevent wildlife and livestock collisions with the train.

The Trans Mongolian Railway crosses Mongolia from Altanbulag to Zamyn-Uud

These fences fulfilled their purpose – albeit with unintended consequences:

Whilst livestock could be led to favourable habitats by their herders, these fences limited the options that wild migratory species such as Mongolian gazelles and Asiatic wild asses (khulans in Mongolian) had to escape the biting winters by migrating towards suitable grazing areas. They were forced to remain in resource-lacking areas; limiting their chances of surviving the harsh winters. In addition, the fences have led to indirect effects by exacerbating existing threats: competition with livestock, poaching, and human developments, to name but a few, can no longer be escaped so easily as before.

Aerial view of the Trans-Mongolian Railway and the associated fences (Photo: Kirk Olson/WCS)

There were no recorded instances of gazelles successfully crossing the fences but the stark evidence of their attempts to resume their migration observed – a number of both species of gazelles have been found entangled in the fences. Not only gazelles but other species were impacted as well. Khulans witnessed their eastern population disappear, provoking a strong ecosystem imbalance.

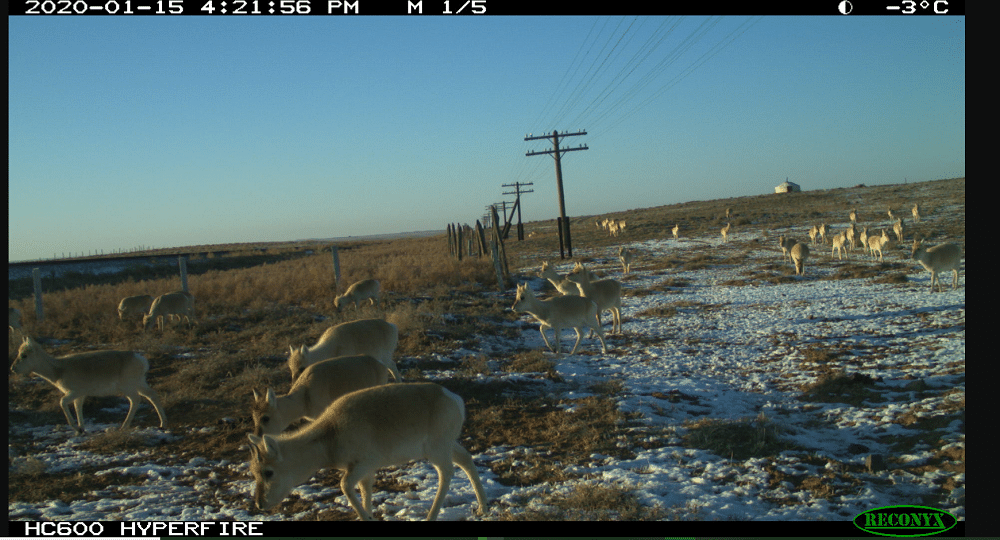

In 2019, a partnership between the Wildlife Conservation Society of Mongolia and the Ulaanbaatar Railroad Authority launched a fence-removal pilot project in an effort to allow the resumption of migrations, with the funding from Oyu Tolgoi LLC. Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Institute, and the Secretariat of the Convention on Migratory Species, and Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA) were also partners to a larger initiative for habitat connectivity restoration. Approximately 1,200 m fences were removed at two locations and more than 100 remote cameras were installed to monitor the use of fence-gaps by wildlife. And it happened! Hundreds of Mongolian gazelles were recorded at the fence-gaps along with fewer goitered gazelles, of which migration was as well limited by fences.

Camera trap image showing Mongolian gazelles using the fence-gaps (Photo: Kirk Olson/WCS)

The study brought up a meaningful sighting as well; the first khulan to cross the railway in the last 65 years, becoming a symbol of hope not only for the eastern khulan population but also for the ecosystem they are part of. As a pilot project, these first two gaps show that gazelles and bigger species such as khulans are able to use fence-gaps. However, researchers believe that these gaps are not of sufficient length to provide crossing opportunities to these species whose movements extend across a broad front, and that additional ones should be implemented.

A khulan as a hope flag: the first individual recorded crossing the railway in the last 65 years (Photo: Kirk Olson/WCS)

How many gaps, and of which length, will be needed in the fence to provide sufficient crossing options to allow nomadic movements such as the migration of Mongolian gazelles to succeed? Will the eastern population of khulan settle again and how will the ecosystem benefit from that return? That is a story to be continued…