On June 17, the Sawfish Project Indonesia team had the wonderful chance to discuss with Mahatub Khan Badhon about his efforts to conserve sawfish in the Bay of Bengal in Bangladesh. Since team members of the Sawfish Project Indonesia have not been involved with conservation projects before, this meeting was a good way for the team to learn about the reality on the ground and the challenges faced by the species in Bangladesh.

Sawfish Project Indonesia is a conservation project initiated by the Conservation Leadership Programme for the Asia & Pacific region. We aim to protect endangered sawfish in the waters of Merauke, Indonesia, by increasing awareness and knowledge of local fishermen, identifying means to reduce the catching of sawfish, and providing policy recommendations for the sustainability of sawfish populations. Since the project has not yet begun due to the pandemic, we took this chance to expand our knowledge and network by reaching out to Mahatub.

An adult and a juvenile sawfish caught in Merauke. Photo: Loka PSPL Sorong.

He told us about some of the challenges that his team experienced when they worked with fishermen in the coastal areas of Bangladesh: “Fishermen don’t actively or intentionally hunt sawfish, rather they get entangled in fishing nets by accident. In case of such an incident, fishermen don’t know what to do with the species even if it remains alive. They don’t want to keep them because catching more commercially-important fish species is more profitable than retaining a sawfish.”

Sawfish are known for their heads that are modified to look like saws. This uniqueness is what makes them more susceptible to entangle themselves in fishing nets. Their saw is also what makes them of high commercial value as some people tend to display and decorate that part of the animal.

However, after sawfish were included in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora list, catching the hunting and trading of the species is now prohibited. Unfortunately, this doesn’t eliminate the risk of by-catch, which is now arguably the biggest factor contributing to their decline worldwide.

Mahatub also explained that no fishing net modification has been developed in order to reduce this risk of by-catch for the species. The only tested approach is to ensure that fishermen are actively engaged with the conservation of sawfish and release the individuals they catch alive back in their natural habitat.

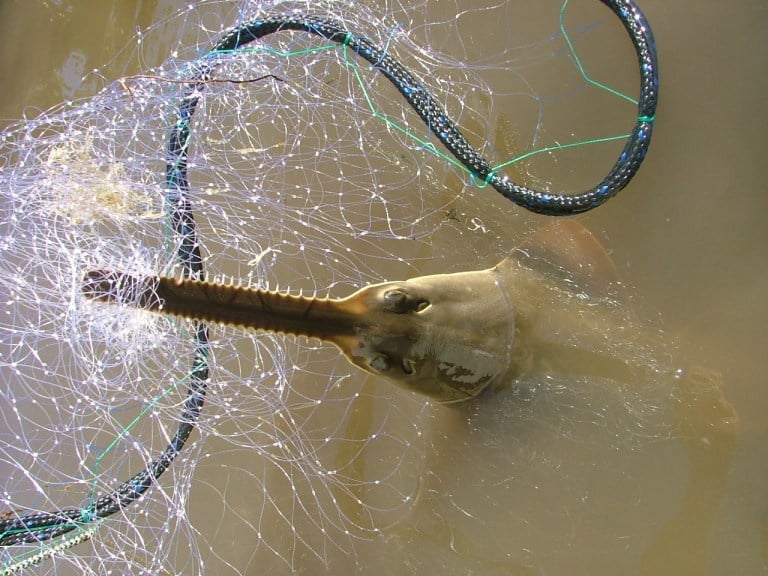

The rostrum of a sawfish can get entangled in fishing nets easily. Photo: Beau-Yeiser.

“But here this challenge starts to get real and difficult”, he added. “The fishermen don’t have any training on releasing the animals alive and they don’t know how to handle them safely. Hence it is wrong and unjust when uninformed and untrained fishermen are lectured or taunted or vilified by conservationists or journalists, and punished by law enforcement authorities for retaining a sawfish.”

Mahatub’s solution to this problem was to collect globally-accepted information on how to safely release sawfish. He and his team spoke to local fishermen who had encountered or handled sawfish first-hand. Both sources complemented each other and helped them to come up with a protocol applicable in the context of Bangladesh.

In order to reach out to more than 60,000 fishing units, they had to come up with a guidebook, a YouTube video, and an Android application in the Bengali language. These education materials are expected to become a basis for fishermen to release sawfish back in Bangladesh.

By using the English transcript of the guidebook and the video developed by the team in Bangladesh we are aiming to prepare similar resources in Indonesian and Papuan languages so that local fishermen in Merauke can also get trained.

Another important aspect emphasized by Mahatub is the importance of the collaboration between the fishermen and the local government. Based on his experience, some fishermen had objections on the damaged nets resulting from releasing sawfish. Indeed, sometimes individuals get entangled so badly that it is impossible to let them go alive without having to cut the net.

The role of the local government becomes crucial in that case and includes: having funds allocated to fishermen so that they can replace damaged fishing nets while releasing sawfish and providing social recognition to fishermen who work together with the government in seeking conservation of protected species. The existence of an interactive collaboration between fishermen and the local government gives a certain ray of hope for sawfish.

A sawfish in its natural habitat. Picture David-Morgan

In the Indonesian context, sawfish are not yet a target for education and conservation. Many higher educational institutions, especially in the field related to marine science, do not mention sawfish in their marine biology courses at all. Additionally, local conservation organizations have not mobilized resources to investigate the latest data on their presence and abundance in Indonesian waters. However, there has been some global attention to the conservation of the sawfish with projects such as the one led by Prof. Colin Simpfendorfer to search for the last remaining sawfish using environmental DNA in various parts of the world.

We are very happy to have a cross-country collaboration with Mahatub. We hope that this project can become an initiator to attract the attention of the Indonesian government and of global stakeholders towards sawfish conservation. Hopefully, we can become an intermediary between fishermen and the local government and contribute to establishing a sustainable partnership in Merauke to protect sawfish.