Ten years ago, the Egyptian Vulture population in eastern Europe was in a freefall because too many birds were killed by human activities all along their migratory route. By expanding conservation efforts across three continents, conservationists have now shown that even such globetrotting species can be saved.

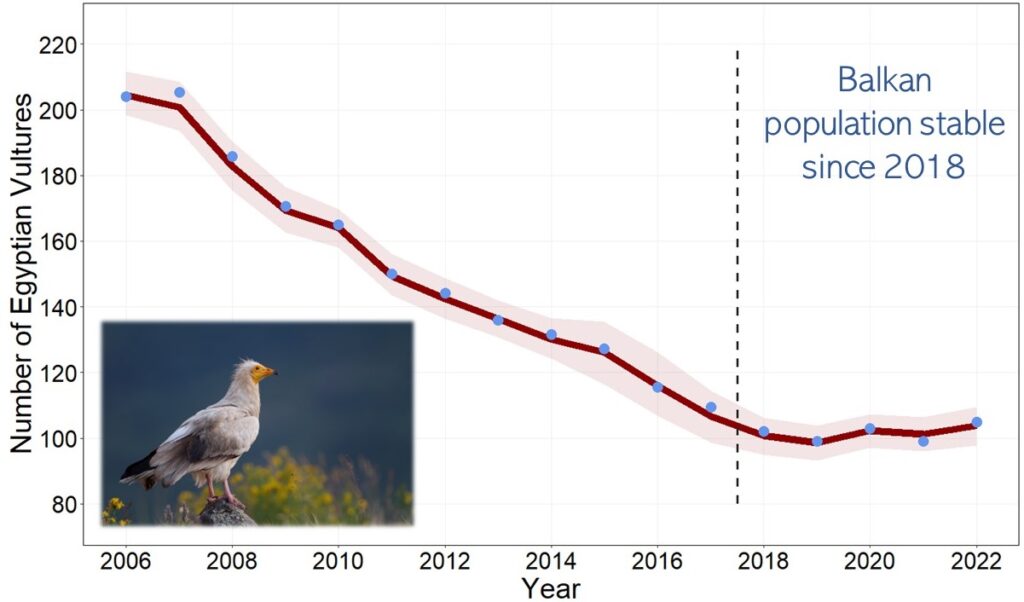

Graph showing population of Egyptian Vulture in the Balkans

Life is inherently risky when the annual routine involves a journey of thousands of kilometres, with the risk of getting shot in one country, poisoned in another, and electrocuted in the remaining dozen countries they cross on the way to more benign wintering climates.

Conservationists often despair at the plight of migratory species. With enormous effort, birds can be protected in either their breeding or wintering areas, but those efforts amount to nothing if the birds vanish whilst on their migratory route.

An adult Egyptian Vulture that died after consuming poisoned bait in Bulgaria – © BSPB

The Egyptian Vulture, Europe´s smallest and only long-distance migratory vulture, is a typical example of a threatened migratory species: in eastern Europe, the population plummeted from >600 pairs in the 1980s to ~50 pairs in 2018. Many threats loom along the entire flyway, from Europe to Africa via the Middle East, contributing to their decline. Since 2010, conservation managers in Bulgaria and Greece have been trying to save the Balkan breeding population. But until 2018, the population was not showing any improvement.

Conservationists in Greece and Bulgaria now use dog patrols to find and remove poisoned baits from the countryside to save vultures – © E. Bantikou / HOS

A project by the European Union then expanded the work along the flyway, involving 22 partners from 14 countries across three continents. A recently published paper in Animal Conservation shows that the population in the Balkans has stabilised since the conservation work expanded from Europe to Middle East and Africa.

Led by conservationists from the Bulgarian Society for the Protection of Birds/BirdLife Bulgaria, the project team reduced the risk of poisoning, electrocution, and direct persecution in 14 countries along the flyway. They also initiated a species reinforcement programme in the Balkans by releasing captive-bred individuals into the wild, donated by the European Endangered Species Programme (EEP) of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). As a consequence, the annual mortality rate of Egyptian Vultures decreased by 2% for adults and 9% for juveniles. Although these changes seem minuscule, they had an encouraging effect: since 2018 the Egyptian Vulture population in the Balkans has remained stable around 50 breeding pairs.

Juvenile and immature Egyptian Vultures from the reinforcement programme – © Volen Arkumarev / BSPB

Arresting the decline of a threatened migratory bird species is a major success, but the team cannot rest on its laurels just yet. Success of such a conservation project requires ongoing work; removing poison from the countryside, reducing illegal killing of birds, and managing the ever-expanding network of poorly located and designed powerlines that become death traps for birds. Persistent efforts to reduce these threats are necessary along the entire flyway to facilitate the recovery of the population. Funding is sorely needed to sustain these efforts.

At the recent Conference of the Parties to the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species, the work of the project team was highlighted which contributed to commitments to strengthen implementation of multi-species action plans. These commitments included a ban on the veterinary use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory drugs, which cause fatal kidney failure in vultures, and phasing out the use of lead ammunition, which can cause lead poisoning in scavenging birds.

Although the Egyptian Vulture population is by no means secure yet, for once there is a glimmer of hope. With a large dedicated team working at truly intercontinental scales, even species that migrate thousands of kilometres can potentially be rescued – a feat that seemed impossible only a few years ago.

The project team equipped >70 Egyptian Vultures with tracking devices to understand their migration and the threats to the population – © Steffen Oppel / RSPB