This FAQ was developed in partnership with researchers from the Interdisciplinary Centre for Conservation Science, the Oxford Martin Programme on the Illegal Wildlife Trade and the Conservation Evidence at the Conservation Science Group from the University of Cambridge .

How did COVID-19 emerge and what is the link with the wildlife trade?

There is still a lot of uncertainty and we might never have a full picture of what happened but here are some of the facts that have been confirmed. Some of the early first cases of COVID-19 recorded were among people who worked in a “wet market” in Wuhan, China. However, it was later identified that some of the first people who had the virus had actually not been at the market. Therefore, even though the market may have played a role in the spreading of the virus, it does not mean that the first transmission took place there.

What has been determined so far is that the virus came from bats and would have been transmitted to humans through another animal species (called an “intermediate host”), which has yet to be identified. A number of researchers have suggested this might be a pangolin because viruses closely related to COVID-19 have been found in some pangolins. As there were wild animals being sold at the market and the virus came from a wild animal, an immediate link was made with trading wildlife commercially and the spread of the virus to humans. But as you can see, this is quite a speculative link.

What is a “wet market” exactly?

“Wet markets” usually include a large number of open-air stalls selling a range of products such as seafood, meat, fruits and vegetables. In some cases, live animals like chicken and fish can also be found at the market and are slaughtered on site. The name originally comes from the observation by British people living in Singapore that people splashed water over their produce to keep it cool, and used water to wash down floors. Though nowadays it’s used to describe a market with fresh produce more generally. Fresh food markets are not specific to China and are found around the world, including in the UK.

A “wet market” might also sell wild animals and their meat. The market in Wuhan, for example, had a section where porcupines, beavers and snakes among other species were kept live and slaughtered. Those markets are, however, less common in China than markets which don’t sell wildlife.

What makes those markets a riskier environment when it comes to zoonotic diseases (diseases passed from an animal to a human)?

Viruses are known to spread more easily when animals are kept in cramped conditions with poor hygiene standards. In a “wet market”, animals are sometimes kept in stacked cages under intense stress. These conditions can make diseases spread more easily; just as if people were in cramped and stressful conditions, our immune systems would suffer, and we would be more likely to catch, and spread, viruses. Once animals are infected, viruses such as COVID-19 can jump to the sellers or buyers as they touch them, because viruses are in all the animal’s bodily fluids (blood, saliva and so on).

However, zoonotic diseases are far from being a new issue. Close interactions with wild animals have been known to cause outbreaks in humans before, with recent examples including Ebola (with the most recent major outbreak in 2014-2016) and Nipah virus.

Would banning wildlife trade completely then avoid any risks of future outbreaks?

Wildlife trade is very broad and diverse. It includes farmers in Africa selling forest rats they have trapped around their fields in local markets, for extra money, as well as people trading ivory in international markets. In Europe it’s quite common to sell mushrooms and deer for food. It also includes wild animals and plants sold for reasons other than food, like pets, medicines, jewellery. So the “wet market” in Wuhan is far from being representative of the wildlife trade as a whole. The disease issue is not with the act of selling wildlife itself but more with bad hygiene conditions which can be associated with this trade, and give opportunities for diseases to spread.

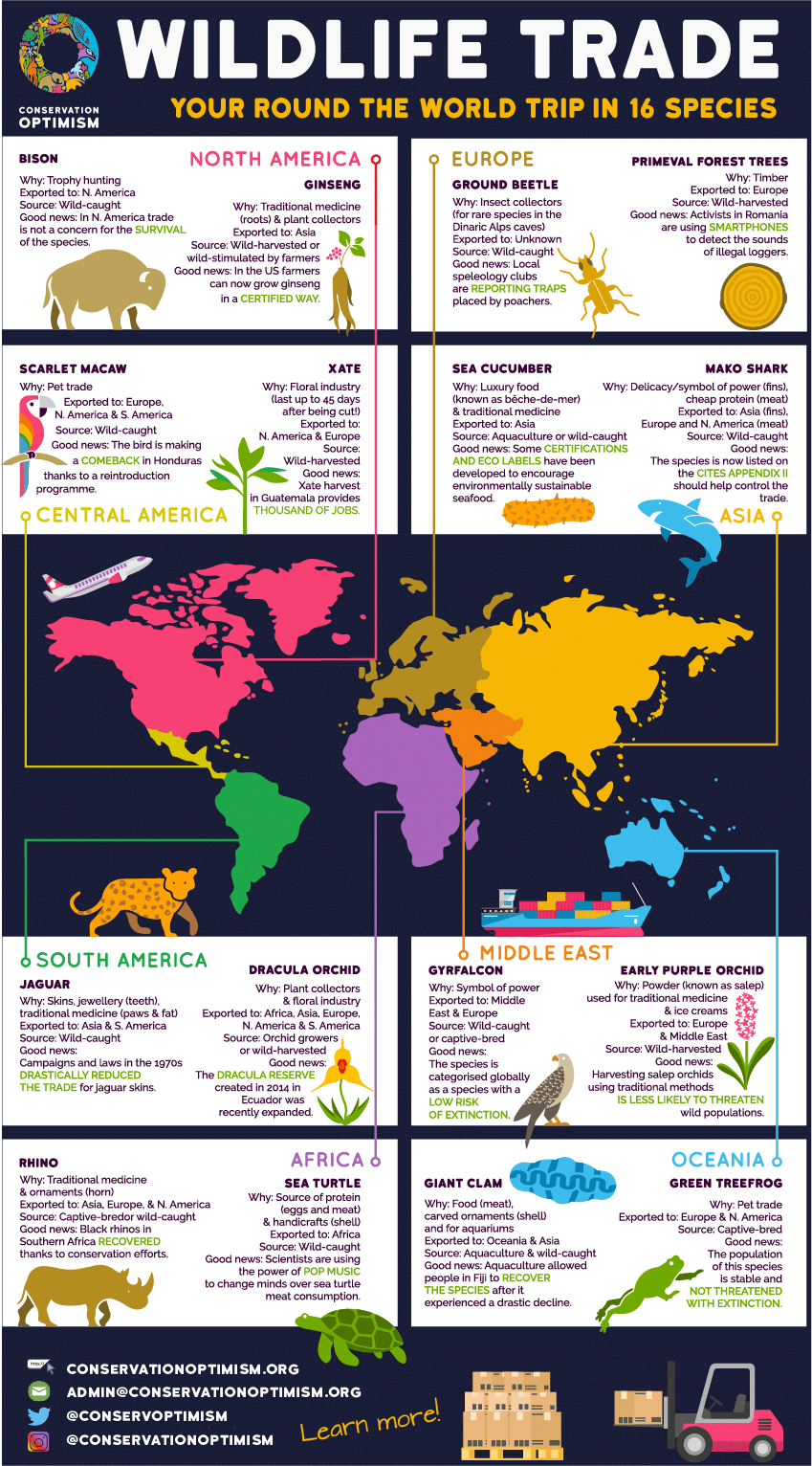

Another important point to keep in mind is that wildlife trade encompasses many species and geographical locations. Banning wildlife trade as a whole won’t work, and trying to do it will have a dramatic impact on people’s lives around the world. Indeed, millions of people worldwide depend on wildlife trade in some way, through either harvesting products, selling them, or consuming them. You can find some examples on the infographic below.

How would a ban affect me here in the UK?

People in the UK buy and sell wildlife very frequently. Some of it comes from the wild, and some of it is reared in captivity. A world where there is no wildlife trade at all would actually mean that nobody can buy or sell wild animals, plants and fungi. If you think about it as someone who shops in the UK that would make a difference even to us. It would affect a range of industries, from food to herbal medicines, and cosmetics (many products contain wild-sourced ingredients). For example, it would mean consumers would not be able to buy pheasants or wild deer from the local butcher. It would also have a big impact on pet shops (think of animals such as lizards, snakes and geckos, which are wild animals even if they’ve been reared in captivity, so would be included in the ban), hugely restricting what they can sell.

What are other ways we can avoid future pandemics if not through a ban on wildlife trade?

Pandemics are not exclusively linked to wildlife consumption and have always been around. Plagues, for example, go as far back as the Neolithic. In 1520, Spanish forces landed in Mexico, and unwittingly brought smallpox with them. The virus is estimated to have killed nearly half of the population (50,000 to 300,000 people) of the capital of the Aztec Empire. The Spanish flu outbreak in 1918 killed more people than the first world war and is considered to be one of the deadliest pandemics in history. Successive plague outbreaks in Europe killed up to half of some countries’ populations.

While we cannot avoid disease outbreaks completely, we can reduce the risk of disease transmission. One way to do this is to make sure that we don’t cause new viruses to jump over from wildlife into domesticated animals and people. That means looking at issues such as agricultural expansion, deforestation, intensive animal agriculture, and other factors that trigger human populations and their animals to live more and more closely to wildlife.

Another important aspect to look into is how to reduce the risk of disease transmission in cases where humans and wildlife do get in contact. If a species is known to have a high risk of transmission then a solution could be to have stronger regulations on trade to stop trading it and replace it with a less risky alternative. Species which might qualify include bats and primates, as these are known to pose higher risks if humans capture and eat them.

Making sure that farms and markets are better regulated is also an important part of the equation. That would mean putting measures in place to reduce the risk of transmission between different species such as keeping wild species separate from domestic ones, increasing distances between individual animals and improving the overall hygiene of the stalls, and market.

More options for preventing future epidemics of zoonotic origin can be found here.

I have read that pangolins were identified as the intermediate host, is that true?

We know that pangolins do host various strains of coronaviruses, so they were thought by some researchers to be a potential intermediate host when the pandemic started. However, there is no evidence so far that they carry the strain that leads to COVID-19. An announcement made earlier this year stating that pangolins had been identified as an intermediate host has since been refuted. While pangolins were tested for coronavirus, there were other mammals present at the market that have not been tested, so that means that a range of other species could have actually been the intermediate host.

If wild animals were kept in better conditions in wet markets would the risk of viral transmission ever be low enough to be considered as an acceptable risk?

Potentially, although some species such as bats, most rodents and primates should probably not be traded at all for human consumption given the complex risks they often pose.

If wild animals were slaughtered before they reach the wet market would the risk of viral transmission be low enough to be considered as an acceptable risk?

If animals were slaughtered in adequately controlled settings before being taken to the market, risks would decrease because it would remove the risk of transmission through scratches or bites and would reduce or eliminate viral release via blood, saliva, urine and faeces. However, fresh carcasses themselves can also be important sources of infection and thus some risks will persist.

Introducing standards of hygiene and traceability are good ways to reduce the risks but are not always realistic or financially doable. Investing funds to improve standards, and working with wildlife harvesters would make it much easier to rapidly trace the source of future infections and prevent further spread if someone was to fall sick.

What other animals and plants are traded in the UK?

Within the UK we trade pheasants and partridges (which are reared commercially but live in the wild before they are shot), wild deer, rabbits and hares, mushrooms, also plants like wild garlic and samphire. Wild foraging is very fashionable at the moment, for farmers’ markets and restaurants.

All sorts of wildlife species are traded into the UK. There is an international UN convention, called CITES, that monitors legal trade of wildlife between countries. Here’s some examples of interesting species that were traded into the UK recently:

* Hippo, bharal, bear (hunting trophies)

* Live snakes (pet trade)

* Crocodile and alligator leather products (commercial)

* Whale skeleton (educational)

* Live gorilla (zoo)

*Orchids (personal, e.g: bringing an orchid bought in another country in the UK)

* Raw corals (commercial and educational)

To what extent are domestic animals prone to hazardous viral infection from wild animals?

There are numerous instances where pathogens are transmitted to humans via domestic animals. For example, Nipah virus passed from bats to domestic pigs before infecting pig farm workers in Malaysia and Singapore in 1999, causing encephalitis and respiratory symptoms, with over 100 people dying as a consequence.

Avian influenza, or bird flu, occurs naturally in wild aquatic birds such as ducks and geese but it can infect domestic poultry with both the low-pathogenicity, and more rarely the highly pathogenic avian influenza A viruses, which can also infect humans.

Even when the disease does not transmit to people the consequences can be very serious. For example, there are currently several outbreaks of African swine fever (ASF) in Europe (with Hungary, Poland and Romania reporting the most number of cases in June 2020). This is often spread from wild boar to farmed pigs and leads to enormous numbers of pigs that have to be culled and their carcasses destroyed in order to control contamination. ASF is far from affecting only Europe. A recent outbreak is estimated to have cut the Chinese pig herd (estimated at 440 million) in half since August 2018. In the US, a study conducted by agricultural economists at Iowa State University has recently estimated that the economic impact of a hypothetical African swine fever (ASF) outbreak in the country could cost the swine industry as much as $50 billion over 10 years!

Why is it important to have accurate information on the link between wildlife trade and coronavirus?

If governments are to make policies that actually work to reduce pandemic disease risk, then they need to know how different potential options will play out. Governments are facing lots of trade-offs, for example how much it costs to implement a law vs how much it would reduce the risk of another pandemic. These decisions need science – we need to give decision-makers an understanding of what effect different options might have, but importantly we also need to tell them where the uncertainties lie.

For example, in the case of wildlife and COVID-19, we don’t know (and we may never know) how COVID-19 got into humans. But we do know that the most likely original source was a bat, and that there was probably some other animal involved in between. We also know that bats harbour lots of coronaviruses, and that there have been other previous bat-borne viruses that have got into humans (like Nipah and MERS). So, more likely than not, there will be other viruses coming from bats into humans unless we change our ways. Mostly that means treating bats with respect – not hunting and trading them, not cutting down their habitat so that they have to find other places to roost. So in the case of bats, the answer might be quite clear, especially as they perform extraordinarily important roles in nature and for humans, including pest control, pollination and seed dispersal. But as you’ve seen from the answers to other questions here, whether or not it makes sense to ban all wildlife trade is a much more difficult question – it may reduce the risk from wildlife inside markets, but it may make little difference if domestic animals fill the gap in unhygienic markets, and may even make things worse if increased livestock farming brings people and wildlife into even closer contact.

Another problem is that all sorts of other issues and agendas get mixed up with these types of discussions. For example, when people think about the wildlife trade, they are rightly concerned about the conservation implications of hunting and trading, and about the welfare of traded animals. This is partly why people are pushing so hard to ban all wildlife trade. But the problem is that approaches that might make things better on one dimension make things worse on another (it’s like squeezing a balloon – you can push it in in one place, and it just pops out in another). Science can help in disentangling the various complicated pathways through which a policy affects wildlife, and then governments need to make decisions about which way to go, to balance all the competing priorities that they have (which will include risk, cost, public opinion and their own moral standpoints).

Why is misinformation and fake news so attractive?

As human beings, we are natural storytellers and as such we can get carried away by powerful narratives. This means that we are naturally more susceptible to false claims as long as they are packaged as riveting stories. The power of social media then helps the spread of those fake news as nowadays a few clicks can make a story go viral at an unprecedented speed.

During the pandemic, many fake stories relating to the environment were in the spotlight and it became hard to sort the truth out from the lies. Fake news was spreading particularly fast when the narrative was about hope and positivity. At a time where people were stuck at home feeling quite gloomy, it is easy to see what might have caused this appeal to fake good environmental news. And the appeal actually seems to grow with exposure. A study from 2018 showed that repeated exposure to fake news headlines (think social media on a loop) makes people more likely to believe them, adding another layer of complexity when it comes to then debunking them!

Wondering if you might have seen some lockdown-related fake news of nature recovery? Go check here and find out some of the most viral fake stories spread during March 2020!