Earlier this month, over 200 social scientists gathered (both virtually and in-person) in Queensland, Australia, to discuss and share their work about the Great Barrier Reef.

In a space usually dominated by the bio-physical sciences, and after months of zoom calls, the hybrid event was a welcome breath of fresh air.

Turtle swimming through the Great Barrier Reef. Credit Yolanda Waters

Social science encompasses a wide range of disciplines – including, but not limited to, political science, economics, sociology, anthropology, and psychology – and its overall purpose is to understand people. Specifically, why do individuals, communities, and organisations do the things that they do and how can we drive better decision-making in complex social, cultural, and political spaces?

Over a day of honest truths, laughter, minor technical glitches, and passionate conversations, the very human solutions to our coral reef crisis were everywhere – from better water quality management and reef restoration to better governance and climate mitigation.

But the ultimate solution was the theme that tied them all together – empathy. The ability to recognise and share feelings with others. It helps build community, evoke emotion, and prompt action. And it could also help save the Great Barrier Reef.

Green Sea Turtle swims along the Great Barrier Reef. Credit: Amanda Cotton

Empathy and connection to nature

The idea that empathy can strengthen human-environment relationships is not new. However, amid several environmental crises and in the rush to save the reef within a decade, it can be easily forgotten. Peta Ross, a proud Juru Traditional Owner and Assistant Director of Indigenous Compliance, GBRMPA, made sure to remind us of this. “Go out there and connect to Country” she said, “remember why you are all here.” She urged us to recognise that in a room full of diverse backgrounds, disciplines and maybe even opinions, the reef, and our connections to it are what brings us all together.

It has been shown that building ocean empathy can help motivate environmental attitudes and behaviour. So, could embracing such empathy in decision-making spaces help drive positive outcomes for the reef? Could greater empathy for the reef help us put competition and politics aside to make better decisions for it? As I watched program managers, directors, professors, and renowned scientists take off their shoes, step onto the grass and look out towards the glassy sea with excitement – I believe the answer is yes.

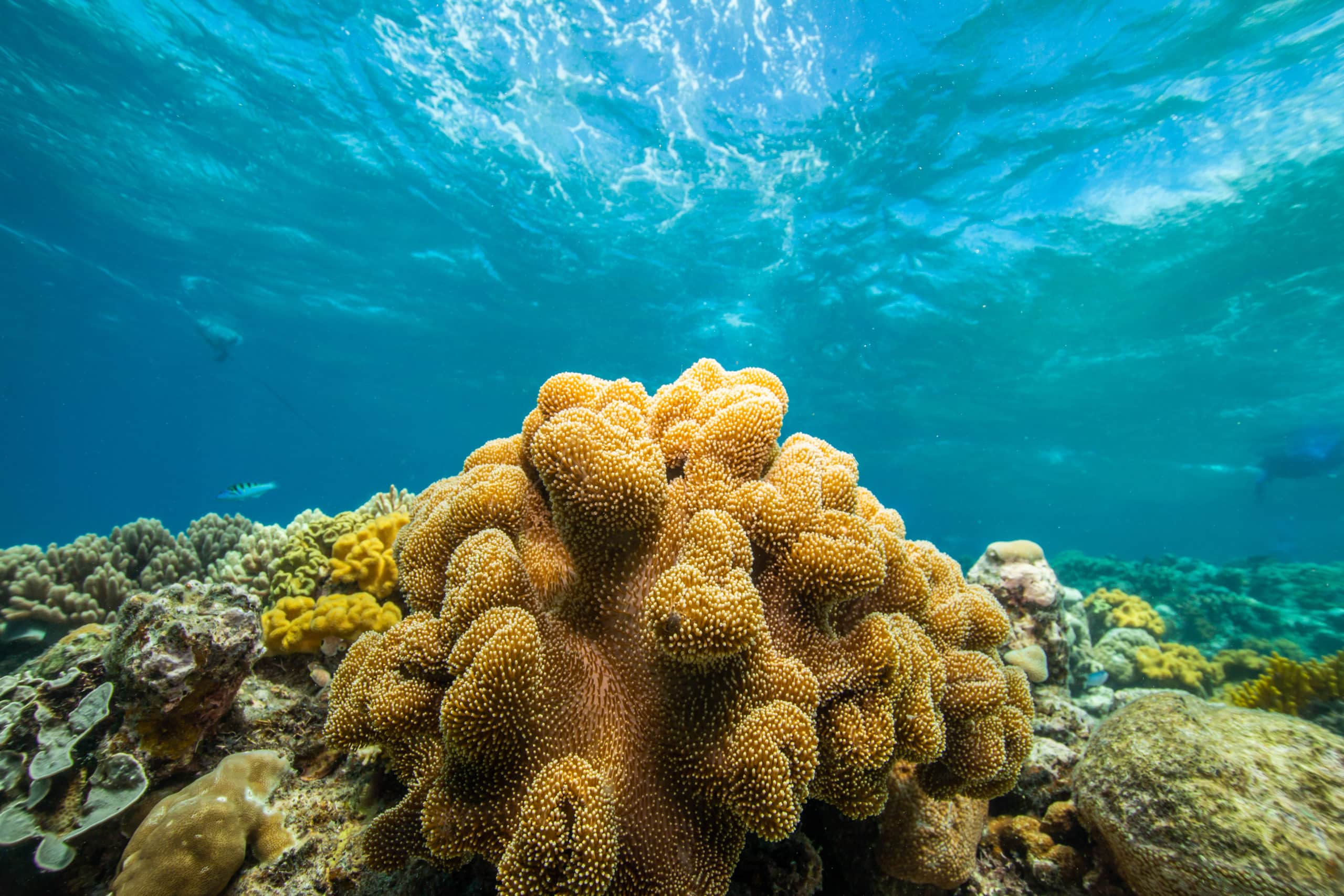

The Great Barrier Reef. Credit Yolanda Waters

Empathy and connection to others

From evaluating reef governance systems, to land management, to restoration, to climate action – every possible solution for the reef is reliant on genuine collaboration and engagement. While on the surface we see this as stakeholder engagement and public deliberation, underneath runs a basic need for trust, respect, and empathy.

For example, understanding stakeholder needs and their capacity for change in an already challenging world; sharing values and finding common ground to build public acceptance of new technologies; understanding the reasons behind different responses to extreme climate events; actively listening to and building trust with Traditional Owners. The list goes on.

Embracing empathy means recognising that we are all fighting for the same goal, while navigating our own lives at the same time. It’s easy to remember that people cause environmental problems. What is harder to remember is that people, real people, are also the ones who can solve them.

The Great Barrier Reef. Credit Yolanda Waters

Empathy and effective communication

Finally, empathy makes us better communicators. And that doesn’t just mean better speakers or presenters, but better listeners. In a panel session, Bob Muir, Woppaburra elder and Indigenous Partnerships Coordinator at AIMS, stressed the importance of simply sitting down to “have a cuppa” and practice active listening. Not only does this build understanding, but it also builds trust and most importantly, it builds respect. Thinking about broader public engagement with the reef and of course, climate change, active listening can also help break through polarising narratives and may even help to cross partisan divides. In the end, the level of collaboration required to save the reef will rely on how effectively we communicate – between stakeholders, between decision-makers and the public, between anyone and everyone who cares about the reef and its future. So, as the natural scientists continue listening and learning from the reef itself, we must also remember to actively listen and learn from each other.

Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Credit: Katerina Katopis / Ocean Image Bank

A key learning from the symposium was that change can be slow and complex, and solving a problem as big as saving the Great Barrier Reef is taxing on everyone – we are all only human. And, while fostering empathy may not help us cross every barrier to change – it is clear that it must be at the core of everything we do.

Thank you to Michelle Dyer and Cindy Huchery for putting together such an inspiring event, and to Peta Ross and Bob Muir for sharing their wisdom and hitting us with some honest and much needed truths.