It is difficult to choose one from the projects presented at the Conservation Optimism Summit, as every one of them held instructing and exemplary elements that I would be happy to share. For me, however, the most momentous were the following:

Personal vocation, courage and endurance are essential in the commencement, organization and fulfilment of a conservation project.

This is shown by the work of Alan Watson Featherstone, who started the restoration of the natural forests of the Scottish Highlands 28 years ago. The work, which seemed quite hopeless at the beginning, is today verified by millions of planted trees, and the spreading success of the nature conservation movement ‘Trees for life’. Kerstin Forsberg also started solo work ten years ago, initially for the protection of the giant oceanic manta ray (Manta birostris). Today, she leads the non-governmental organization Planeta Océano (Planet Ocean), which reaches hundreds of thousands of people, and, thanks to its activity, in Peru, knowledge of marine biology has become part of the public education agenda. Good examples are set forth by the increasing number of individual farmers, too, who carry out their work with consideration to the conservation of natural values, or with the explicit aim of restoring natural ecosystems. One of them is Sir Charlie Burrell, English landowner and farmer, who, for 15 years, on his own land of the Knepp Castle Estate, has been developing his farming methods, focused on nature conservation, in line with the ‘wilderness’ concept, designed by ecological researcher Frans Vera.

Today it is beyond doubt that communication and education are essential in conservation activity.

The aim of this activity is partly to increase awareness of the problem, and partly to mould the thinking and behaviour of those directly concerned, as well as the general public, and to enhance responsibility for nature conservation. The latter is of utmost importance, as the strength and abilities of individual committed persons are insufficient for the thorough resolution of problems. For this, the key lies in common language, frankness, and respectful communication. This has also been confirmed by the opinion of Hungarian conservation experts, when asked about the treatment of wood pastures (Varga et al. 2017). The conference, not at all by chance, was opened by the lecture of Niki Harré, psychologist and professor at the University of Auckland, who also called attention to communication, exaggerated expectations towards others, and the acknowledgement of our own barriers. She offers advice on the establishment of a “sustainable and happy” lifestyle (Harré 2011). In the course of nature conservation activities, in order to solve conflicts arising from insufficient communication, the concerned groups are invited to common thinking. The concerned groups may include anyone from one’s own children (Conservation Sisters) to office worker consumers living at the other end of the world, so the communication strategies applied and presented are also versatile.

Collaborating with arts and gastronomy is an uncommon, but none the less efficient way of communication.

Nessie Reid, from Bristol, England, tried to raise awareness of extensive animal farming and the importance of healthy food with her art performance ‘The Milking Parlour’. She moved into Bristol’s main square for a week together with two cows, milked them, drank their milk, and held lectures and free discussions about the topic. The success of using arts is partly due to their ability to provide space and the means to discuss difficult topics and situations. Artistic interventions also open up new perspectives, facilitating better understanding of a topic. The importance of arts and gastronomy was the central idea at several of the conference sessions. Gastronomy concerns and connects everyone, as healthy and tasty food is good for all. I talked about this, among other things, in my lecture. Wood pastures are habitats of outstanding natural and cultural value, and their maintenance is highly dependent on grazing and the consumption of its products (gastro tv show – Gastro angel – food from the Hungarian wood pastures).

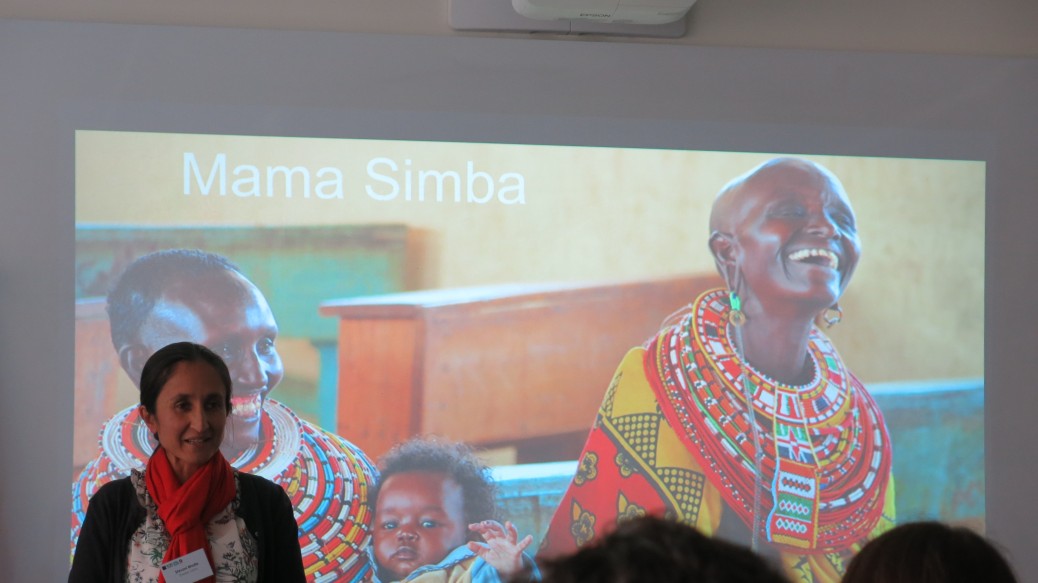

Among all the good examples shared, I was most fascinated by the cooperation of researchers, nature conservationists, and locals, fighting for the protection of the lions of Kenya. For local pastoralist and hunting tribes, lions only ever meant a problem and an enemy, and this without the majority of the locals having ever set eyes on a lion. This train of thought, namely, that “nature means and causes trouble”, which mainly concerns predators and taxa called “dangerous”, is obviously a basic obstacle for nature conservation. (We witnessed something of the sort in Hungary by the Tisza River (2nd river of Hungary), around 2006. We realized that the inhabitants of the riverside settlements, having abandoned utilization of the floodplains, had lost all connection with the river, and only “met” the water at times of flood, which do cause and mean trouble.) One of the first steps taken by the workers of the Kenyan ‘Ewaso Lions’ project was to acquaint the locals with the lions. As an important element of this, they organized lion-watching camps for children, so that they could meet real lions. The success of these camps began to arouse the interest of other members of the community, and after a while, from among the young men entering warrior age, a lion keeper group has been organized, and mothers have also founded a group (Mama Simba), on their own initiative. Today, locals know and record all the lions individually, and the loss of one of them is badly felt by the entire community.

In Protecting lions, not only did the local community become stronger, but conservationists and researchers alike have been flooded by hope and optimism.

No-one can single-handedly stop global processes, such as the destruction and building over of habitats, but on the local level, one can share the joys and griefs of the protection of the lions with the people who share their habitat every day. It is obvious that children and adults of the area realized that when protecting the lions, they also protect their own communities, culture, and the landscape that is home for them as well. According to the project leader, the key to success was respecting the values, culture, and habits of the local community at all times. They laid emphasis on the thorough involvement of locals, who have been granted freedom to execute their own ideas harmonizing with lion protection. In the past months, I had the chance to participate in a cooperation for a high nature and cultural value ancient wood pasture, the Kasztó , in the vicinity of Bogyiszló village (for the example of a superb project with the local, public school about the biocultural heritage of the local ancient wood pastures).

Witnessing the devotion and interest of local residents, and the power of education and arts in forming their attitude, all confirmed in me the validity of the lessons of the conference. For successful nature conservation, which is valid ground for our optimism, the only way leads through thorough knowledge of the problem, including local factors, personal and community level commitment, conscious, respectful and dedicated communication, education, and a community that supports and recognizes its members.