At Re-Peat we believe that peatlands are a lens through which we can imagine a new future. Sounds weird? Let me explain what we mean.

Firstly – what’s a peatland? Peatlands are a type of wetland with a permanently high water table. This means when plants die and fall below the water’s surface, rather than being decomposed by microorganisms (and the carbon in their bodies released back into the atmosphere) they simply remain, because the microorganisms do not have enough oxygen due to the water. Through this process, peat forms, causing peatlands to be the largest terrestrial carbon store when wet but a disproportionate carbon source when degraded.

The thing about peatlands is that they suck you in. The more you read and hear about, the more their magic reveals itself to you – like staring at a patch of earth and watching minute insects, mosses and lichens multiply and diversify as your eyes adjust to the smaller scale. Peatlands are not just immense carbon stores but also purify drinking water, mitigate flooding, cool the local environment, protect astonishing archaeological remains and provide a home for rare species that have adapted to the peatland’s waterlogged conditions. Yet despite all this, 15% of peatlands globally are drained, with 80% of the UK’s peatlands in a degraded state.

Peatlands, wetlands with permanently high water table, form large terrestrial carbon stores which become major carbon sources when degraded. Credit: Re-Peat

Re-Peat is a youth-led collective that was founded in late 2019 following a guided tour round a local peatland in Amsterdam. This provoked the two questions that everyone asks when they first learn about peatlands. (1) Why have I never heard of these things!? And (2) how can something this valuable be mistreated?

Re-Peat makes the following suggestion as an answer to (2). Read a book or watch a film that features a swamp, marsh, moor, or bog and most of the time the key characteristics of that place will be barrenness and danger. At worse, peatlands are portrayed as places to be wary of and keep away from. At best they are blank, devoid. This representation means that conversion of a peatland into something else – an agricultural field, a wind-farm, a peat-mine, a forest– is often permissible. If there is nothing of value here, or if the place is outright ‘bad’, then how can we be doing any harm by changing it? A peatland paradigm shift is needed, where people see peatlands not as wastelands but rather in their true fullness of value, as places we and other species depend on. Then, they might be treated better.

In answer to question (1) – you haven’t heard about them because not enough people are talking about them! That is why the first of the three entwined approaches Re-Peat takes to bring about this paradigm shift is education. The more people know about peatlands, the better. And when it comes to peatlands there really is something for everyone. It only takes a few surprising facts for people to get hooked in by peatlands, and then they find themselves sinking in the mushy moss, neck-deep in the fascinating ecology, history, hydrology or even poetry of peatlands.

“They are both an archive of ancient humanity and a developing record of how we are changing our environment.” Picture Credit: Re-Peat

Next, we go one step further and encourage an active re-imagining of the way the world is and the way the future could be. Peatlands are lenses through which to imagine a new future because they are places where possibilities are particularly numerous and open. Peatlands are both deeply terrestrial (they are defined by their soil) and fundamentally aquatic (they are permanently wet). They are wide and open, as well as intricate and intimate. They are both an archive of ancient humanity and a developing record of how we are changing our environment.

As young people we are often told that we are being unrealistic or idealistic when we ask for a sustainable future, but the paradoxes of peatlands increase the space for what is considered possible. Peatlands allow us to imagine radically optimistic futures, where they and the rest of the natural world are engaged with in a paradigm of reciprocity, benefiting both human and non-human life. Re-Peat facilitates this re-imagining through creative exercises and projects.

The final strand cohering this all together is collaboration. We seek out and give a platform to people working to protect, restore or study peatlands around the world. Together we co-create the paradigm shift, multiplying our influence beyond what we could achieve in isolation.

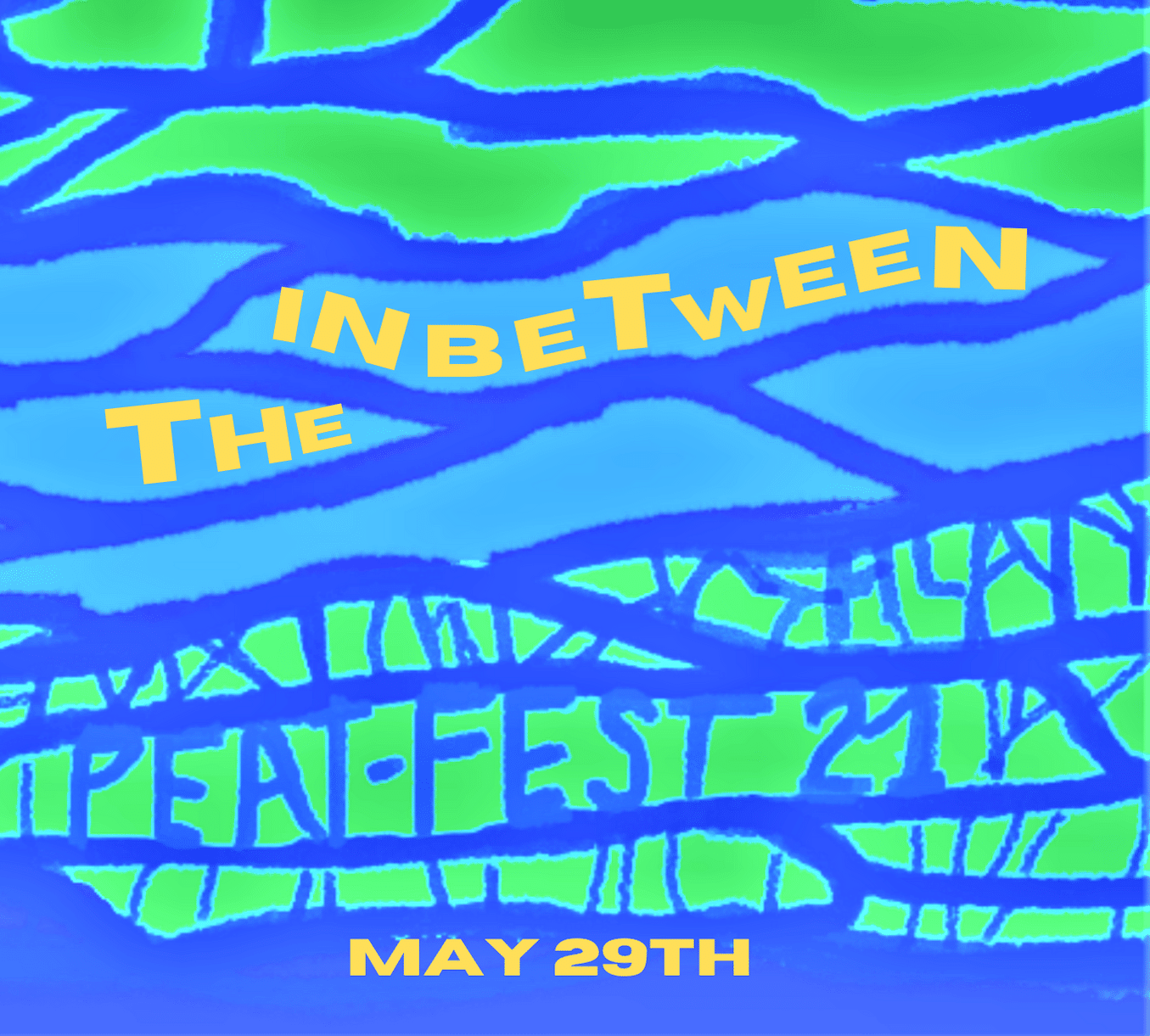

Peat-Fest, on 29th of May, is a 24 hour online festival with participants from all over the globe, completely dedicated to peatlands.

The biggest and craziest manifestation of this strategy is Peat-Fest, a 24 hour online festival, with participants from all over the globe, completely dedicated to peatlands. This year, Peat-Fest is on the 29th May and will include talks from Peter McCoy, author of Radical Mycology, on the fungi of peatlands, Congo-Peat, on the extraordinary peatlands of the Congo basin (the largest peatland network in the world), Dr. Bin Xu on peatland restoration in Western Canada – and MUCH MORE!

We are excited to connect with ConservationNOW and collaborate with such a wide group of inspiring people who share our vision of an optimistic future where all of nature, including peatlands, is treated with the value we know it holds.

Get tickets to Peat-Fest here: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/peat-fest-2021-tickets-152743599217?aff=ebdsoporgprofile