Nukus, the little-known capital of Karakalpakstan region, Uzbekistan, has a remarkable and unexpected collection of modern art, created by Igor Savitsky in this remote refuge at a time when such art was discouraged by the Soviet state. Wandering around it, I saw early 20th century paintings of the huge Amu Darya river stretching to the horizon, with fishing vessels, busy ports and markets, and people strolling and working in the shade of trees.

The next day we drove through dusty surburbs and salt-crusted fields, the result of Stalin’s policy to replace the extensive Tugai forest of the Amu Darya river delta with cotton fields. We were listening to Oktyabr’, tour guide and archaeologist from the Uzbekistan Academy of Sciences, who grew up in Muinak town, the centre of the huge ecological and social catastrophe that was the drying of the Aral sea. We already knew the basic story, but it was another thing to hear first-hand about his childhood friend who ran the last fish cannery in Muinak, and killed himself when it finally closed a few years ago, with the loss of 2,000 local jobs. Or how both his parents died in their early fifties from cancers caused by the pesticide-laden dust. And how in the old days, it was a huge port and naval base, where all the men from the region embarked to fight in the second world war. People came from all over the USSR to join the commercial fishing fleet, which sent canned fish back to the whole Soviet Union and its allies, while caviar was so commonplace that his mother baked it into bread.

Fishing vessel, Muinak, 1970 (by Vadim Madgazin).

Abandoned ship at Muinak, May 2018.

The death of this part of the Aral Sea was caused by over-extraction of water from the Amu Darya river for cotton production (with associated heavy chemical usage). This was compounded by large-scale extraction by countries upstream, and more recently by climate change leading to less snow in the Pamir mountains and less rain throughout the region. The river now peters out in Nukus, 200 km south of Muinak.

The end of the Amu Darya river, Nukus.

The Soviets’ first reaction to the unfolding crisis was to build a canal from the strategically important port of Muinak to the receding sea, but the water left so quickly that after 25 km they had to give up. For a while, the canneries received fish from other places, but finally they too had to admit defeat. Walking among the boats placed on the sea bottom, below the cliff where Muinak’s lighthouse stands, we were reminded of Shelley’s poem Ozymandias:

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Ships’ graveyard on the sea bottom, Muinak.

We were in Muinak to hold a celebration for schoolchildren promoting saiga antelope conservation, and discuss ways to work together. The school is small and old, with limed walls, and the town has shrunk to a picturesque village, with single-storey white-painted adobe houses. A few tourists come to visit the abandoned ships, but there’s nothing to keep them here.

A picture of saigas by a child from Muinak school.

The visit to the school was touching and uplifting, because of the huge excitement that the children and teachers showed for our visit, demonstrated in the pictures they had drawn of a species none of them is likely to have seen. Saigas cling on in Uzbekistan, with most of them now in the new desert which is the bed of the Aral sea, because it is challenging for poachers to access. So my colleagues at the Saiga Conservation Alliance want to work with these children and their teachers to make poaching socially unacceptable.

As we travelled back to Nukus that evening, I felt perversely optimistic, in the face of one of the most obvious and devastating recent demonstrations of human mismanagement in the world. Although visiting the school and seeing the potential for transformative ecological education was lovely, it was more than that. It was not just that we could see that efforts to vegetate the sea bottom were bearing fruit. The artificial waterbodies near Muinak, made to mitigate polluted dust storms, were beautiful and bouncing with birds, which raised my spirits, but that too is not enough.

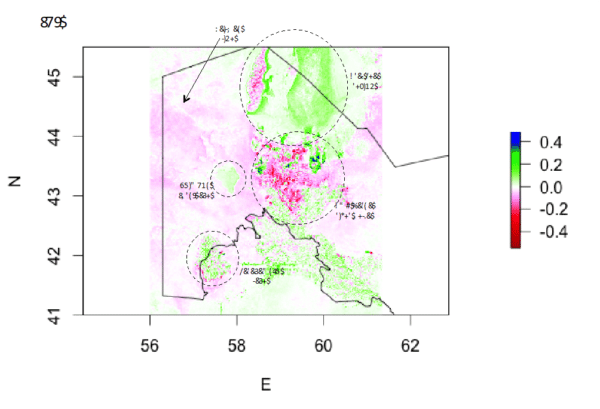

Trends in NDVI from Modis images, 2001-2012, showing greening of the former sea even as the delta dries (from Bull et al. 2015, Land Use Policy).

New vegetation on the Aral sea bottom resulting from a seed distribution programme, seen from the causeway road to Muinak.

This area has a long history of large-scale devastation, putting into context the wanton waste of resources and consequent ecological and social damage of the recent past. In the 8th century, Arab conquerors swept away the Zoroastrian culture and its monuments. In the 13th century Ghengis Khan devastated the canal systems that brought life to large areas, as well as the cities and their cultural landmarks, imprinting his own vision. Traces of both previous cultures underlie current land- and cityscapes. We were seeing the results of Soviet megalomania at Muinak, and we were told of the impending demolition by the current regime of culturally and socially important areas of the country’s ancient cities in a push towards mass market tourism. Sweeping environmental change is also characteristic; until the 15th Century, the Amu Darya drained into the Caspian sea. When it shifted to the Aral sea, leaving cities and silk routes dessicated, the Aral sea grew and the new delta filled with life. So in this desert land, the fertile, productive Amu Darya delta and sea which I saw in the Savitsky paintings were also transient. The landscapes and people of this region are resilient to these endless batterings of large-scale ecological and political forces over which they have no control. Resilience can, however, tip over into fatalism.

So, does the optimistic future for the Aral sea region lie in sensible environmental management at the large and small scales, allowing more water to flow (international water use agreements, national redirection of agriculture away from cotton and rice to more sustainable crops, local adoption of less wasteful and damaging irrigation techniques)? Probably not, in the short term, as fundamental changes in governance would be needed, of which we see no sign. Is the Aral sea region going to become an ecologically resilient, protected, safe haven for threatened species like the saiga? The chances are slim. Are the children of Muinak school going to have a healthy and fulfilling future in their home town, with good employment? Unlikely.

The main cause for optimism is that there are a few people in Uzbekistan, like my Saiga Conservation Alliance colleagues, who have a vision for the future, and demonstrate in small ways how it could be realised. They chip away at institutional, personal and social inertia, through events like Saiga Day which tell children, teachers, and indirectly parents, that nature is precious, its casual destruction is wrong, and together we can change the future. They lobby the government for protected status for areas harbouring precious remnants of natural value like the saiga. They instill professional pride into rangers and border guards. They develop enterprises for local women making high quality handicrafts. They are ready to exploit opportunities such as changes of mood in government, or strong new actors (like the gas companies which are increasingly dominant forces in rural areas). There are also international NGOs like the Wildlife Conservation Network, whose staff came with us to Muinak to see our work first-hand, and who see the value of investing in those with vision in apparently hopeless situations.

Nature and people persist, albeit diminished. There is plenty that can be done to improve things now, even with our limited capacity, and system state can change rapidly with a prod at the right time. Although the path to an ecologically bountiful and socially prosperous future for Karakalpakstan is narrow, twisted, rocky, and is blocked and reblocked, my tough and resilient colleagues keep on picking their way through. That’s conservation optimism.

Children in Muinak school.