Conservation works. We know how to bring species back from the brink of extinction, prevent deforestation, eradicate dangerous invasives and protect the most precious places. Our biodiversity crisis may be worsening, but only because conservation remains a niche activity operating at the very periphery of society. Annual global conservation expenditures, for example, were around $1.4 billion in the decade to 2003, somewhat less than the amount spent in the UK every year on ice cream. Does the world really only care as much about maintaining a living planet as British people care about ice cream?

Well, there are signs that this may be changing. A wave of popular environmental activism has swept the world in 2019, led by the Greta Thunberg-inspired School Strike for Climate, Ende Gelände in Germany, the Sunrise Movement in the USA, and Extinction Rebellion.

Extinction Rebellion was formed in May 2018 by a small group of veteran British activists, using evidence on the history of non-violent civil disobedience to design an uprising with the maximum chance of catalysing change. In October that year, the group publically declared themselves to be in open rebellion against the UK government in response to its inaction on climate and ecological breakdown. They went on to carry out a number of high-profile acts of non-violent civil disobedience. In the biggest of these, tens of thousands of activists blockaded four sites in London for 11 days in April 2019, leading to over 1,100 arrests (but zero injuries) in the largest act of civil disobedience in modern British history.

Charlie Gardner next to the pink boat named after murdered Honduran environmental activist Berta Caceres, at the International Rebellion in Oxford Circus, London, April 2019 (Credit: Louise Gardner).

And it has worked – at least partly. The protests catapulted the environment, and the climate crisis in particular, into the public consciousness and up the media and political agenda. Within weeks, the environment had become the third most pressing issue for British voters, above immigration, the economy and crime. And government at all levels is responding: over half the local authorities in the UK have now declared a climate emergency, and in June the UK became the first major economy to enshrine a deadline to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions into law.

But what has all this got to do with conservation? Quite a lot as it happens, for Extinction Rebellion isn’t just a climate movement. It is also a movement for biodiversity, as quotes from its Declaration of Rebellion make clear:

‘The science is clear: we are in the sixth mass extinction event and we will face catastrophe if we do not act swiftly and robustly.’ […]

‘Biodiversity is being annihilated around the world. Our seas are poisoned, acidic and rising.’ […]

‘The ecological crises that are impacting upon this nation, and indeed this planet and its wildlife can no longer be ignored, denied nor go unanswered by any beings of sound rational thought, ethical conscience, moral concern, or spiritual belief.’ […]

‘In accordance with these values, the virtues of truth and the weight of scientific evidence, we declare it our duty to act on behalf of the security and well-being of our children, our communities and the future of the planet itself.’ […]

‘We hereby declare the bonds of the social contract to be null and void, which the government has rendered invalid by its continuing failure to act appropriately. We call upon every principled and peaceful citizen to rise with us.

We demand to be heard, to apply informed solutions to these ecological crises and to create a national assembly by which to initiate those solutions needed to change our present cataclysmic course.

We refuse to bequeath a dying planet to future generations by failing to act now.

We act in peace, with ferocious love of these lands in our hearts. We act on behalf of life.’

These are powerful words. Tear-inducing words. The day many of us have dreamed of, the day when ordinary people would care about nature as we do, is finally here. Today, members of the public care so much about biodiversity loss that they are prepared to take to the streets for it, and even risk arrest and imprisonment. Watching a funeral procession for lost species making its way around Parliament Square in April, it was clear that we would be niche no more. Conservation is going mainstream.

Claire Wordley at an Extinction Rebellion Protest at Blackfriar’s Bridge, London, in November 2018. (Image credit: Jane Carpenter)

Oddly, and with few exceptions, conservationists have remained conspicuously silent throughout all this. At actions we have met grandparents and schoolchildren, City professionals and hippies, but conservationists seem thin on the ground. Nor is there much visible support for the Rebellion amongst our colleagues, whether conservation scientists or practitioners. After decades of trying to communicate the severity of our environmental crises to the public, our message seems finally to have got through, yet we are nowhere to be seen.

This is more than a missed opportunity; it is a dereliction of our moral duty. As scientists and conservationists we have told people the facts, and we must now stand by those so concerned by what we’ve told them that they’ve taken to the streets. This is what we argue in an opinion piece published this month in Nature Ecology and Evolution, in which we encourage scientists (and by extension conservationists) to embrace civil disobedience. The paper clearly struck a chord. It was tweeted over 2500 times within 10 days of publication and has attained an Altmetric ‘attention score’ that places it in the top 0.009% of papers tracked by the metric. An accompanying op-ed in The Guardian has been shared over 1250 times.

Our involvement in movements like Extinction Rebellion can enhance their credibility and effectiveness. By making the sacrifice of taking time to engage in protest, we send a strong ‘costly signal’, which can persuade others of how seriously conservationists take the threats we face. And, importantly, we can help ensure that the emphasis on the ecological crisis remains as strong as that on the climate crisis.

Moreover, involvement can be extremely rewarding on a personal level. It feels good to be part of something bigger, something powerful that might just trigger the radical changes we need, and the hopefulness this generates is both invigorating and energising. Both of us have found profound meaning and joy in becoming part of a community willing to take big risks to conserve our beautiful planet – this has helped to replace despondency with courage, and despair with determination.

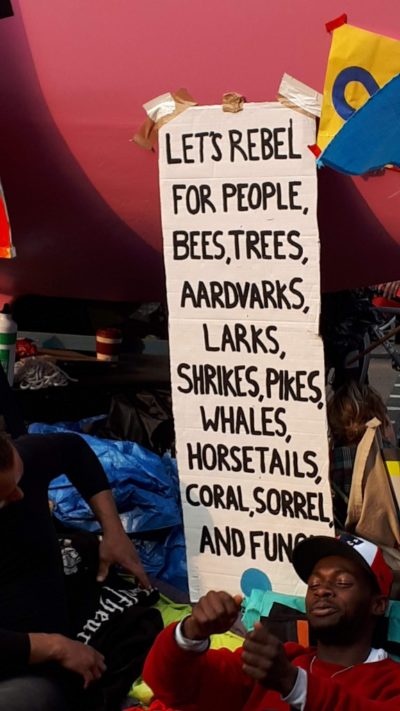

A sign next to the pink boat named after murdered Honduran environmental activist Berta Caceres, at the International Rebellion in Oxford Circus, London, April 2019 (Credit: Louise Gardner)

As conservationists and members of Extinction Rebellion, we urge you to get involved. The next International Rebellion begins in London and globally on 7th October, and it is going to be huge. We will go to our capital cities, camp in the streets, and shut down business as usual. It will be an unmissable festival of life.

Participation does not mean having to risk arrest: all those arrested in April had volunteered to do so and received training. For every one of them there were many others in key support roles, and dozens more who just came along to show support and enjoy the car-free streets. There are lots of ways conservationists can support preparation or take part in the event itself, but even just being there and taking the time to speak to bystanders will be immensely worthwhile. If you can’t make it to your capital city you can contribute remotely, and express your support online, among friends, and to the media. Beyond that you can join your local group, or start your own if there isn’t one – one of us did after the April Rebellion, and the group now has over 200 members and has made it into the local papers about 30 times in just four months.

Conservation is effective, but we will only be able to maintain a living planet and avoid the loss of a million species if we can get conservation issues into the mainstream. We need to drive the political will to put biodiversity and environmental sustainability at the heart of policy-making. Writing another paper won’t do that, and neither will signing petitions, sending emails, donating to advocacy groups or marching from A to B. But civil disobedience just might.

The choice is simple – extinction, or rebellion.